I presented the following prediction as part of a spirited Churchill Club debate with 5 other VCs. It was first published as text in AllThingsD.

Remember MS-DOS commands, and the WordStar keystroke combinations we had to memorize? Then the first Macintosh featured a mouse driven GUI that was game changing because it removed a layer of friction for both the data going in and coming out. When we tried that first model, we knew we could never go back to a C prompt.

And yet the impact of graphical computing was minor compared to how facial computing will change our lives, and how we all relate to The Collective. Think of it as a man-in-the-middle attack on our senses, intercepting all the signals we see and hear, and enhancing them before they reach our brains.

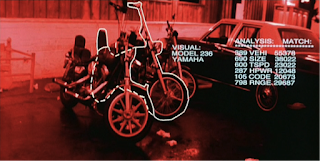

|

| First Generation Mobile Computer |

This is not science fiction, and based on prototypes I’ve seen, it’s a good bet that design teams in Google, Apple, Samsung and various military contractors are building eyewear computers that will render smartphones as obsolete as the first generation of mobile computer. I’m not talking about Google Glass, with its cute little screen in the corner. I mean an immersive experience that processes what we see, and then overlays graphical objects onto our field of view: true Terminator Vision. The US military has this capability today, so that troops can see pointers to their platoon members, and markers of known IED locations. So now it’s just a question of making the hardware small, cheap, and available in four adorable colors.

Not only will our favorite apps on eyewear computers be more immediate and engaging, but we’ll experience new computing capabilities so compelling that we find them indispensible. For example, eyewear computers can record our lives, and enable us to summon any relevant conversation or incident from our past. With eyewear computers, we can truly share experiences in real time, transporting ourselves to the perspective of someone on a ski slope, or in a night club, Wimbledon match, or the International Space Station.

Just as Terminator did in the movie, we will air-click on actual things we see to interact with, investigate, or purchase. We’ll integrate facial recognition and CRM for background data on everyone we meet. When we travel abroad, signs will appear to us in English, and when someone is speaking to us, we can simply turn on English subtitles.

A new generation of games will be more immersive and engaging than ever before.