Wednesday, 10 February 2010

TED 2010: What the World Needs Now

Wednesday, 3 February 2010

Stopping a Runaway Toyota

One of the terrible accidents reported in the NY Times a few days ago described a 911 call from a panic-stricken driver (an off-duty police officer). He was screaming into the phone that the car was accelerating, that he could not stop it, and that the brakes wouldn't work. The call ended with the sound of a crash. He and his three passengers were all killed instantly.

As the stories unfold in the press, the problem is not restricted to the accelerator pedal, but also includes the brakes. Toyota has known of both problems for many years, but has tried to minimize it. For example, it usually blamed sudden acceleration on floor mats getting stuck on the pedal. However, in several accidents, there were no mats in the car (or they were found in the trunk). It is still minimizing the problem, claiming that the replacement of the current gas pedal will do the trick, even though this fix has failed before, and there is no hard evidence that that is actually the problem.

Moreover, the reports of brake failure cannot be explained by faulty gas pedals. The driver on the 911 call reported that the brakes were not working, and there are multiple stories elsewhere to the same effect.

The US National Traffic Safety Administration thinks that electromagnetic fields may be fouling the electronic circuits. Toyota denies this possibility (see yesterday's NY Times). But if this is the case, no cosmetic fixes like replacing gas pedals is going to work. Moreover, the problem may extend to every car manufactured today with electronic circuitry that controls its operations.

When I first started driving, several centuries ago, the gas pedal was connected to the fuel pump by mechanical means. Today, the gas pedal depresses a sensor, which sends a signal to the computer board. This board processes this signal, along with all of the other data being fed to it from other sensors, and determines how much gasoline and air to feed to the engine. It then sends another electric signal to a fuel injector than controls how much of the gas/air mixture is fed to the engine.

There is a similar situation with brakes and steering. Until about the 1950’s, when power assisted brakes and power assisted steering became available, both braking and steering were purely mechanical procedures. The brake pedal was connected physically to the brakes, and the steering wheel mechanism was directly connected to the front axle. Today, both the brake pedal and the steering wheel operate motors which do most of the braking and steering. You might still be able to operate the brakes and steering when the engine is off, but it would take a great deal of strength to do that, too much to be useful during an emergency.

We all know the frustration when our personal computers crash or freeze up. It happens all the time. In almost every case, it is just an inconvenience. We re-boot and the worst possibility is the loss of some data or the corruption of a file. When the computer in an engine in an automobile going 60 miles per hour “crashes”, so does the vehicle, and the damage to the occupants goes beyond an inconvenience.

What is amazing is that we have been using these devices in our automobiles for so many years and they have not failed more often than they do.

The possibility that electromagnetic fields can cause the electronics to fail is downright scary, We live in a sea of magnetic fields. Radio and TV signals, cell phone calls, overhead power lines, even sun spots generate these fields. The list is endless. While most of the fields are pretty weak, the effect may be cumulative. Moreover, we have no idea how many times we pass through much stronger fields during the day as we go by facilities using high energy equipment. Imagine the consternation in Silicon Valley if it turns out that the IPhone being used by an occupant in the automobile (not just the driver) is responsible! (Maybe that's why the Woz reported today that his own Prius has an overactive accelerator.)

It seems to this writer that this problem is not going to be solved by replacing a gas pedal. Worse, if it is a problem with the electronic circuitry, many other automobile manufacturers may find that they have similar problems. At the least, new cars will have to have better shielding for the electronics, as well as better redundancy and fail-safe systems, including perhaps, manual cutoffs operable from the driver’s position.

In the meantime, what should you do if you are in a car that starts to accelerate and you cannot control it?

Whether or not you think that you have a car that might have this kind of problem, you should still have a plan of action in mind should the situation arise. All the drivers in the family should go over this. You may also want to verify with your mechanic whether these work. Not every model of automobile will respond the same and the efficacy of these suggestions might have to be varied to account for the differences in your particular car. Don't be surprised if the mechanic doesn't know all of this, or only repeats the Toyota press releases. (If he just assures you that Toyota has already solved the problem, consider getting another mechanic.)

If the engine is racing out of control and the brakes won't work there are two possible ways to bring the car under control.

1) The better and safer method is the following:

MOVE THE TRANSMISSION TO NEUTRAL.

This should work in all models. However, verify with your mechanic, or try it yourself at a low speed on a clear road. It is conceivable that, on some models, the transmission level merely operates some electronic circuits, like the gas pedal, in which case you might not be able to shift gears, either. I just don’t know.

Assuming that you are able to get the transmission into neutral, the engine will still be racing at full throttle, but it won’t be sending any power to the wheels. Unless there is something terribly wrong with all of the electronics in the car, and not just the engine circuit boards, the brakes and steering will continue to work properly, and you will retain full control over the vehicle. You should be able to stop it within a hundred feet or so. Even if the power brakes fail (as happened in some of the accidents reported in the newspapers), the car will eventually slow down by itself. You can also try to use the brakes manually—difficult without power brakes but not impossible—and apply the hand brake.

2) Another method, but clearly inferior, is to try to turn off the engine. If you can, the car will stop accelerating (unless you are going down a steep hill). But this won’t slow the car down very quickly (unless you are going uphill). There is still the problem of trying to stop it before it hits something really hard. If the engine is off, the power assists to both the brakes and the steering will be disabled, making it difficult to use the brakes and the steering. Depending on the design of the engine circuitry, the brakes might not work at all. If this happens, you can try applying the parking brake, although this is usually a very weak brake and it would take much longer to bring the car to a halt using this method. Finally, if none of the brakes work, you would just have to let the car roll to a stop. If it is going over 60 miles an hour on a level grade when you cut the engine, it could take a mile or more to stop the car this way. (My 1991 Mazda, which gets up to 38 miles to the gallon, might go 10 miles before stopping; my SUV, which gets 8 miles to the gallon, would probably stop in about 10 feet.)

Without power steering, you may still be able to control the steering at higher speeds (over 20 miles an hour), although you probably will need a significant amount of brute force to do this. When the car speed drops below 20, it will become harder and harder to control the steering wheel, but not necessarily impossible. Just takes even more force. Again, your car mechanic will know how the steering on your car would work if the engine is off.

The bottom line on this technique is that it is better than nothing, but can give you a lot of difficulty maintaining braking and steering control.

You should verify all of these suggestions with a mechanic who understands how the engine, steering and brakes in your particular car are wired up.

Meanwhile, all class action plaintiffs’ attorneys, rev up your engines. Your “action” is just beginning.

Sunday, 24 January 2010

In a Liquidity Crisis, Who Will Buy?

Who Will Buy, by the Avery Buddy Quartet.

Ten-year-old Avery Cowan leads his quartet in their rendition of Who Will Buy, from the musical Oliver. Rob Sequiera sings baritone, Tom Shields sings bass, and Dave Binetti sings tenor.

Tuesday, 12 January 2010

Escape to Maui

Monday, 16 November 2009

I'm gonna sing about baby Jesus!

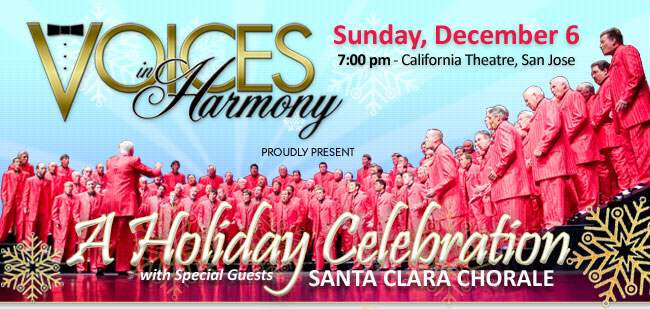

Nothing says "Holiday" better than the rich a capella sound of 72 Christians, four Jews and an atheist. Under the direction of Dr. Greg Lyne, Voices in Harmony will perform a variety of traditional seasonal works including "It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year" (Pola and Wyle), "Hallelujah Chorus" (Handel), "Hodie Christus Natus Est" (Gregorian Chant), and the obligatory Hanukah number Feast of Lights. Joining as special guests are the Santa Clara Chorale under the direction of Ryan James Brandau, performing several outstanding pieces including "Ave Maria" (Busto). Plus, there will be a kids' chorus, and a sing-a-long!

PURCHASE BY PHONE

(408)792-4111

Tickets are also available at the

SJ Convention Center Box Office and Ticketmaster locations.

Box Office hours are Monday - Friday, 9am to 5pm

For more information, visit us at www.vihchorus.org or

![]()

![]()

Sunday, 15 November 2009

Gladwell's Igon Value Problem

For years I've felt quite alone in my opinion that Malcolm Gladwell is a fake (merely one rung above Victoria Knight-McDowell and Kevin Trudeau, and only because Gladwell probably believes his own claptrap). After all, he sells a gazillion books, and speaks at TED (although Karen Amrstrong does both as well, so there you go).

That's why it was great to read Harvard Professor Steven Pinker’s review of Gladwell’s latest product, What The Dog Saw, in today's New York Times Book Review.

Gladwell frequently holds forth about statistics and psychology, and his lack of technical grounding in these subjects can be jarring. He provides misleading definitions of “homology,” “saggital plane” and “power law” and quotes an expert speaking about an “igon value” (that’s eigenvalue, a basic concept in linear algebra). In the spirit of Gladwell, who likes to give portentous names to his aperçus, I will call this the Igon Value Problem: when a writer’s education on a topic consists in interviewing an expert, he is apt to offer generalizations that are banal, obtuse or flat wrong.

...The problem with Gladwell’s generalizations about prediction is that he never zeroes in on the essence of a statistical problem and instead overinterprets some of its trappings... Gladwell bamboozles his readers with pseudoparadoxes...

For example, Gladwell observes that teaching qualification tests are imperfect indicators of success, and concludes therefore that they shouldn’t be used at all. Instead “teaching should be open to anyone with a pulse and a college degree,” whose first year results should serve as the basis for future employment. That is a provocative sound bite that sounds wise if you assess it for no longer than it takes to Blink! But Gladwell neglects to consider the costs of such a tactic, nor the impact on the poor students who are subjected to all those failed first year experiments. Who has time for this? By Gladwell’s logic, based on their imperfections we should dispense entirely with the police department, antibiotics and Hillary Clinton.

Does today's book review mean that my view of Gladwell is no longer an Outlier? If Pinker reaches enough readers, perhaps we'll see a Tipping Point…