This post is only for people who consume healthcare services.

It is well understood that our nation's healthcare delivery system is in crisis, but you may not realize the degree to which it is about to impact families. Health insurance costs per employee are rising between 10% and 20% every year, and healthcare spending per capita is 16.3 times 1970 levels, bringing us to more than twice the average for western world countries. As the costs per employee rise above a certain threshold, employers pass on the deficit to employees, and so the inflation rate of out-of-pocket health costs is even higher. The US Census Bureau forecasts a stunning picture: out-of-pocket expenditures per US family has risen from 13.1% of median income in 1999 to 21.1% in 2003, and

heading north of 30% by 2006. According UCLA's Center for Health Policy Research, in just two years between 2001 and 2003, the average California worker's contribution for family coverage plans rose 79% -- from $114 to $204 per month.

We all recognize, from first-hand experience, the root of the problem. Insurance companies control which doctors we can see, when we can see them, what treatments and medicines they can prescribe, which hospitals we can use, how long we can stay, what tests they can run, how much we pay, etc. As a result, the whole system is, well, completely fucked up.

The ability for consumers to make rational decisions in a free market normally governs the rate of inflation to a reasonable level. Even expensive, complex purchases, such as real estate, taxation, estate planning, investments, home renovation, etc. can be made so long as the consumer has access to professional counsel from practitioners who compete on price, service, and a reputation for dispensing quality advice. But consumers do not have access to an open, freely competitive market for medical services. Our employers choose our plan, our PPO or HMO chooses our doctors, and to keep the PPO patients flowing, doctors comply with the PPO guidelines rather than dispense unencumbered advice. You rarely even have the choice of paying for preventive medicine today to avoid expensive, dangerous treatments later (at which point, figures your insurance company, you are highly likely to be Someone Else's Problem).

But whatchya gonna do? No one wants to start picking up the tab for medical services. Is the whole mess just a necessary evil of the third-party payor system? No!

In fact, there is a promising movement afoot to fix the system that is quickly gaining ground. It is known as Consumer Directed Healthcare (aka Consumer Driven Healthcare, CDH). The goal of CDH is to put the consumer in the driver's seat, so that (s)he is motivated and able to make free, rational choices, while still relying on one's employer to cover the expense using pre-tax dollars. The idea is for employers to purchase very high-deductible (and inexpensive) plans for employees, and to set aside the savings for the consumers to spend themselves on any expenses below the deductible. In the event of grave illness, the old third-party payor system kicks in, but for most families, the healthcare decisions reside in the hands of the consumer. Critically important, whetever you don't spend this year remains available for future years, even if you change employers, so you're motivated to factor in costs as well as quality and service.

Fortunately, in an extremely rare show of wisdom, the Republican US Congress passed a Medicare Modernization Act that legalized CDH funding plans known as Health Savings Accounts (HSA). Employers can buy high-deductible plans, and contribute as much as the deductible itself into the employee's HSA tax-free (federal, soon state). Since the act became effective on Jan 1, 2004, HSA adoption has exploded. By March of this year the number of HSA-covered lives exceeded a million with a 250% annual growth rate.

This comprehensive study on CDH reveals some promising results among early adopters. Employers are saving 20% on healthcare costs, and premiums for high-deductible HSA-elgibile plans rose only 4-6% or, by

some estimates, even dropped 15% this year. Over half of the consumers have money left over after 12 months, accumulating wealth for future years. A

McKinsey study found that HSA account holders are 20% more likely to comply with treatment regimens for chronic conditions. HSA account holders are 50% more likely to inquire about cost, 100% more likely to inquire about drug costs, and 30% more likely to get physical exams. And most importantly, health outcomes are equivalent or better.

Contrary to concerns that HSA's would appeal only to the young, rich and healthy, a study by the consortium America's Health Insurance Plans found that most of the million HSA account holders among its members' insured lives were over 40, 73% of them had children, and 29% had family incomes below $50,000.

So what's the catch? Some people worry that consumers NEED insurance companies telling them and their doctors what to do. Ridiculous. It's certainly hard to make the best decisions about healthcare, but a decision reached by a consumer advised by a licensed doctor of choice has to be at least as good as the same decision constrained by the one-size-fits-all, cost-cutting guidelines of an insurance company.

Having said that, consumers are unaccustomed to shopping for medical services, and there are no available data on the price, quality and service of competing providers. McKinsey's study concluded that "this is the huge challenge of the CDHC movement. If consumers are to welcome new incentives to manage their health care and spending, they must have better information to support their decisions." (

source)

This sounds like a job for "the Internets". Shopping portals have simplified all kinds of complex purchases. And healthcare expenditures are certainly high enough and important enough to drive consumers to whatever comparable data are available.

Meanwhile, get your company, or your family, an HSA and an HSA-eligible plan. I did, and now my family is saving anywhere from $2,000 to $4,000 per year on healthcare, depending upon whether we hit the deductible. And until we hit the deductible, we decide for ourselves which doctors, tests, treatments, drugs and hospital to use.

My next post will point you where to go for an HSA plan, and also tell you how Bessemer hopes to play a critical role in the CDH movement.

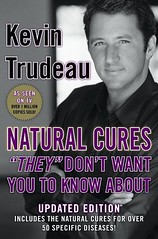

Here's a sickening reminder of how easy it is to scam a public that doesn't understand science. Amazingly, this snake oil brochure is Number 1 on the NY Times Best-Seller list of How-To books. How is it that anyone can trust the prescriptions of a convicted fraudster with no scientific or clinical background?

Here's a sickening reminder of how easy it is to scam a public that doesn't understand science. Amazingly, this snake oil brochure is Number 1 on the NY Times Best-Seller list of How-To books. How is it that anyone can trust the prescriptions of a convicted fraudster with no scientific or clinical background?